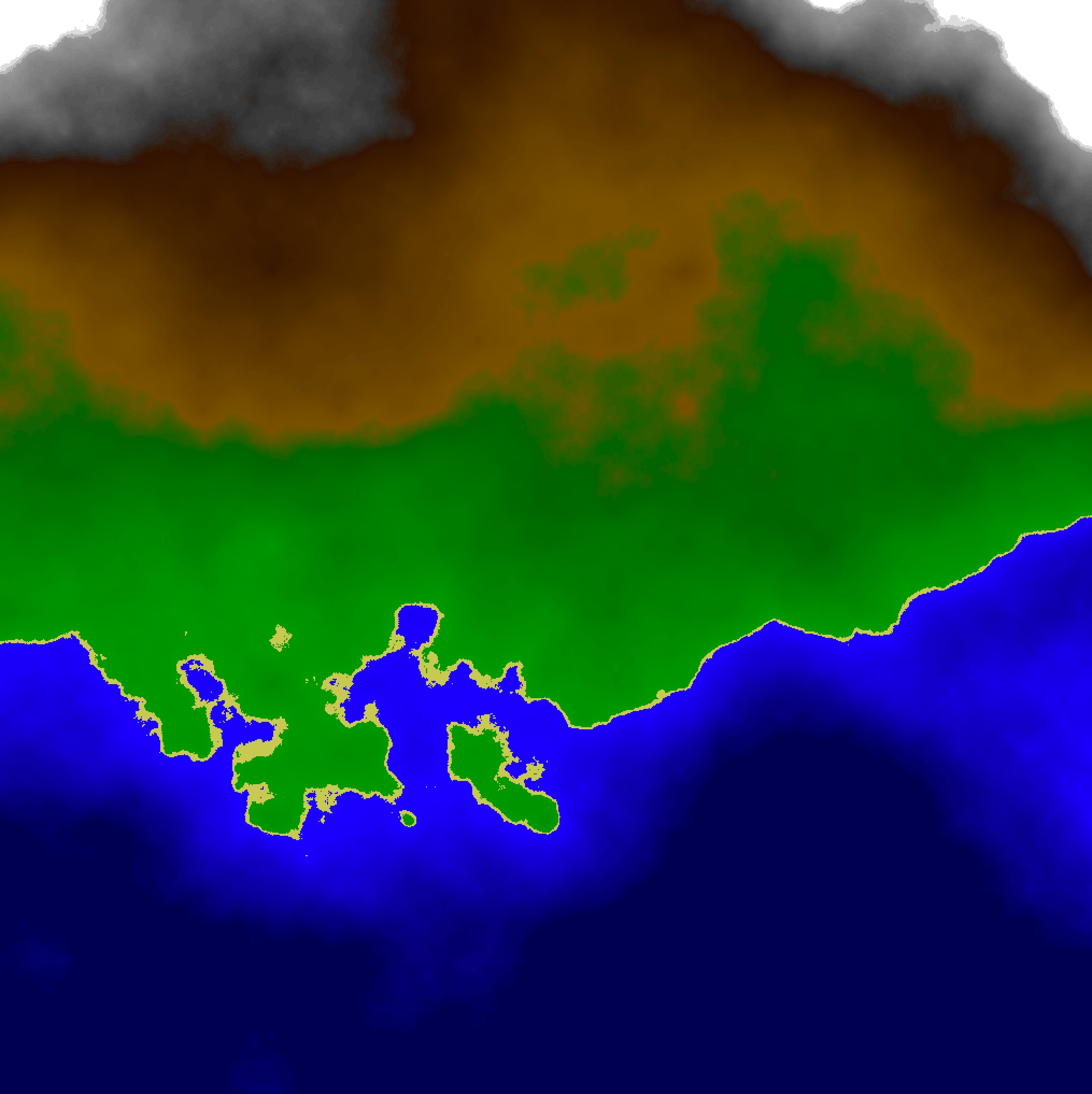

Have you ever wondered how the terrain in games like Minecraft is generated? There’s an old algorithm called the Diamond-Square Algorithm that is in common use. I thought it would be fun to implement this algorithm using TDD. Here’s a sample output from the result:

So I thought you might like to see the TDD steps I used to build this algorithm. Before we start, make sure you understand the algorithm by reading the link above. Don’t worry, it’s a very simple algorithm; and the linked article is extremely easy to read.

So how do you test-drive an algorithm like this? At first it might seem simple. For each test, create an small array of doubles, predict the results, and then write the test that compares the predicted results with the output of the algorithm.

There are several problems with this approach. The first is data-overload. Even the smallest array is a 3X3 with 9 different values to check. The next smallest is 5X5 with 25 values. Then 9X9 with 81 values. Trying to write a comprehensive set of tests, even for the 3X3 case, would be tedious at best; and very difficult for someone else to understand.

The second problem is that test-driving from the raw results forces us to write the whole algorithm very early in the testing process. There’s no way to proceed incrementally. You may recall from previous blogs I’ve written that I call this: “Getting Stuck”.

Yet another problem is that those tests don’t prove the the algorithm is working the way it is supposed to. They just prove that the resulting values are right. Now in most cases that’s not a problem. I’m a strong adherent of the Classical School of TDD, and I tend not to use my tests to inspect the internal workings of the software I am writing. The output values are usually good enough. In this case, however, the algorithm is the overriding concern.

Now, being that I am a classicist, I still want to check values. However, the values I want to check are not the output values of the algorithm, but the internal values that the algorithm uses. Specifically the coordinates of the cells that are being manipulated.

Consider: I want to know that the coordinates of the midpoint of the square are being calculated properly. I also want to ensure that the value of the midpoint is set by taking the average of the four corners. So I’m very interested in the calculation of the coordinates of those four corners. On the other hand, once I know that those coordinates are calculated properly, I don’t really care what the values of the cells are, or whether the average is calculated properly. I mean, averages are pretty trivial to test. So I really don’t need to test the average calculation yet.

The Diamond half of the algorithm has similar concerns. I want to make sure that the coordinates of the diamond points are being calculated properly, and that the coordinates for the inputs to those averages are calculated correctly. I also want to make sure that the diamonds at the edges of the array only draw from the three real points; and don’t try to reach outside the array for the fourth.

So, here’s the code for my tests. I’m not going to show you the code for the actual algorithm; because it’s not particularly interesting. Indeed, I suggest you use these tests to drive your own implementation. ;-)

The Code

We begin by using Stephan Bechtold’s wonderful HierarchicalContextRunner to help us organize our tests. If you aren’t familiar with this runner – shame on you. <grin>

Note the String named actions. This is going to be the heart of our strategy.

@RunWith(HierarchicalContextRunner.class)

public class TerrainInterpolatorTest {

private String actions = "";

private double[][] dummy;

private TerrainInterpolator interpolator;

We start with simple validations. Our setup for this set of tests creates an instance of TerrainInterpolatorSpy, which you’ll see down at the end of the code. This test double is going to load that actions string with the values that we want to test.

This is a rather different slant an a spy test double. Rather than giving us booleans and flags to inspect about the calls of individual functions, this spy is going to load the actions string with the sequence of things that happened as the algorithm proceeded.

The first three tests are just very simple checks to make sure that the algorithm behaves properly when given invalid inputs.

public class SimpleValidations {

@Before

public void setUp() throws Exception {

dummy = new double[1][1];

interpolator = new TerrainInterpolatorSpy();

}

First we test that when we are given an array that’s too small, no actions take place.

@Test

public void terminalCondition_sizeOne() throws Exception {

interpolator.interpolate(dummy, 1);

assertThat(actions, isEmptyString());

}

The next two tests make sure we can detect that the array has an invalid size.

@Test(expected = TerrainInterpolator.BadSize.class)

public void sizeMustBePowerOfTwoPlus1() throws Exception {

interpolator.interpolate(dummy, 2);

}

@Test

public void Check_isPowerOfTwo() throws Exception {

assertThat(interpolator.isPowerOfTwo(2), is(true));

assertThat(interpolator.isPowerOfTwo(4), is(true));

assertThat(interpolator.isPowerOfTwo(8), is(true));

assertThat(interpolator.isPowerOfTwo(1), is(false));

assertThat(interpolator.isPowerOfTwo(7), is(false));

assertThat(interpolator.isPowerOfTwo(18), is(false));

}

Now, on to the real work. We’re going to look at the coordinate calculations. We start by making sure that the midpoint of a 3X3 square is calculated properly, and that the points passed to the average function are the correct points. Stare at that string below until you understand what it means. The code that builds the action string is in the TerrainInterpolatorSpy below.

public class SquareDiamondCoordinateCalculations {

@Test

public void simpleThreeByThree_SquarePass() {

interpolator.interpolate(dummy, 3);

assertThat(actions, startsWith(

"Square(0,0,3): A([0,0],[2,0],[0,2],[2,2])->[1,1]."));

}

Next, we make sure that the diamond points are calculated properly, that the inputs to the average function come from the right locations, and that, since all the diamonds on a 3X3 are on the edges, that the averages are taken from only three points.

@Test

public void simpleThreeByThree_DiamondPass() {

interpolator.interpolate(dummy, 3);

assertThat(actions, endsWith("Diamond(0,0,3): "+

"A([0,0],[2,0],[1,1])->[1,0]. " +

"A([1,1],[0,0],[0,2])->[0,1]. " +

"A([0,2],[2,2],[1,1])->[1,2]. " +

"A([1,1],[2,0],[2,2])->[2,1]. "));

}

Next, let’s look at a 5X5 and make sure that the initial square and diamond coordinates are properly calculated.

@Test

public void DiamondSquare_FirstPass() throws Exception {

interpolator.interpolate(dummy, 5);

assertThat(actions, startsWith(

"Square(0,0,5): A([0,0],[4,0],[0,4],[4,4])->[2,2]. "+

"Diamond(0,0,5): " +

"A([0,0],[4,0],[2,2])->[2,0]. " +

"A([2,2],[0,0],[0,4])->[0,2]. " +

"A([0,4],[4,4],[2,2])->[2,4]. " +

"A([2,2],[4,0],[4,4])->[4,2]. "));

}

}

OK, now we have to make sure that the square and diamonds are properly repeated, with the right size and locations. At this point we don’t care about the averages anymore because we know the coordinates for the inputs are calculated correctly. All we care about now is that the starting points, and sizes for the squares and diamonds are calculated properly. So we’re going to use a different spy. The TerrainInterpolatorDiamondSquareSpy loads the actions string with only the square and diamond actions, but not the averages.

public class SquareDiamondRepetition {

@Before

public void setup() {

dummy = new double[1][1];

interpolator =

new TerrainInterpolatorDiamondSquareSpy();

}

@Test

public void FiveByFive() throws Exception {

interpolator.interpolate(dummy, 5);

assertThat(actions, is(

"" +

"Square(0,0,5) Diamond(0,0,5) " +

"Square(0,0,3) Square(0,2,3) Square(2,0,3) Square(2,2,3) " +

"Diamond(0,0,3) Diamond(0,2,3) Diamond(2,0,3) Diamond(2,2,3) "

));

} }

Now, finally, we can look at some real values. This will help us test-drive the simple stuff, like computing averages from a list of points.

public class Averages {

@Before

public void setup() {

dummy = new double[3][3];

interpolator = new TerrainInterpolator();

}

The call to interpolate with just two arguments, turns off any randomization. Thus, if we start with an array of all zeros; our result should be an array of all zeros.

@Test

public void zero() throws Exception {

interpolator.interpolate(dummy, 3);

assertThat(dummy, is(new double[][]

{{0, 0, 0}, {0, 0, 0}, {0, 0, 0}}));

}

Of course the same is true of all ones. Indeed, an array of all X will produce an array of all X.

@Test

public void allOnes() throws Exception {

dummy[0][0] = dummy[2][0] =

dummy[0][2] = dummy[2][2] = 1;

interpolator.interpolate(dummy, 3);

assertThat(dummy, is(new double[][]{

{1, 1, 1},

{1, 1, 1},

{1, 1, 1}}));

}

Now for some real math.

@Test

public void ramp() throws Exception {

dummy[0][0] = 0;

dummy[2][0] = 12;

dummy[0][2] = 12;

dummy[2][2] = 24;

interpolator.interpolate(dummy,3);

assertThat(dummy, is(new double[][]{

{0, 8, 12},

{8, 12, 16},

{12, 16, 24}}));

}

}

OK, finally, let’s make sure the random factor and offset are being added properly. The offset is my own creation, so that I can drive the values up or down with a fixed offset. The third argument to the interpolate call is the random amplitude. The fourth is the offset. The TerrainInterpolatorWithFixedRandom test double simply turns off the randomness, and uses the absolute values of the random amplitude instead.

This test took a lot of hand calculation to create. And, of course, I did the calculation wrong, at first. So then I had to check the results from the algorithm, and modify the test.

public class RandomsAndOffsets {

@Before

public void setup() {

dummy = new double[5][5];

interpolator =

new TerrainInterpolatorWithFixedRandom();

}

@Test

public void volcano() throws Exception {

interpolator.interpolate(dummy, 5, 2,4);

assertThat(dummy, is(new double[][]{

{0,8.5,8,8.5,0},

{8.5,8.5,10.75,8.5,8.5},

{8,10.75,6,10.75,8},

{8.5,8.5,10.75,8.5,8.5},

{0,8.5,8,8.5,0}

}));

}

}

}

The TerrainInterpolatorSpy loads the actions variable with the square, diamond, set, and average actions invoked by the algorithm. This test double simply overrides those functions of the main algorithm with others that load the actions variable.

private class TerrainInterpolatorSpy

extends TerrainInterpolator {

void doSquare(int x, int y, int size) {

actions += String.format("Square(%d,%d,%d): ",x,y,size);

super.doSquare(x, y, size);

}

void doDiamond(int x, int y, int size) {

actions += String.format(

"Diamond(%d,%d,%d): ",x,y,size);

super.doDiamond(x, y, size);

}

void set(int x, int y, double value) {

actions += String.format("->[%d,%d]. ", x, y);

}

double get(int x, int y) {

return -1;

}

double average(Integer... points) {

actions += "A(";

for (int i = 0; i < points.length; i += 2)

actions += String.format(

"[%d,%d],", points[i], points[i + 1]);

actions = actions.substring(0, actions.length()-1)+")";

return 0;

}

}

The TerrainInterploatorDiamondSquareSpy test double simply loads the actions variable with the square and diamond actions; but not with the set or average actions.

private class TerrainInterpolatorDiamondSquareSpy

extends TerrainInterpolator {

void doSquare(int x, int y, int size) {

actions += String.format("Square(%d,%d,%d) ",x,y,size);

}

void doDiamond(int x, int y, int size) {

actions += String.format("Diamond(%d,%d,%d) ",x,y,size);

}

}

The TerrainInterpolatorWithFixedRandom test double simply overrides the random function to return the fixed randomAmplitude instead of returning a random number between + and - randomAmplitude.

private class TerrainInterpolatorWithFixedRandom

extends TerrainInterpolator {

double random() {

return randomAmplitude;

}

}

}

From these tests I created a fully functioning DiamondSquare algorithm. I bet you can too. Give it a try.