The following is a segment of a journey. It has no obvious beginning point, nor does it actually end up anywhere. The value, if any, is in the journey itself.

The code below is the standard solution to the Prime Factors Kata.

public List<Integer> factorsOf(int n) {

ArrayList<Integer> factors = new ArrayList<>();

for (int d = 2; n > 1; d++)

for (; n % d == 0; n /= d)

factors.add(d);

return factors;

}

However, I was doing this kata in Clojure the other day and I wound up with a different solution. It looked like this:

(defn prime-factors [n]

(loop [n n d 2 factors []]

(if (> n 1)

(if (zero? (mod n d))

(recur (/ n d) d (conj factors d))

(recur n (inc d) factors))

factors)))

The algorithm is pretty much the same. I mean if you tracked the value of n, d, and factors they would go through the same changes. On the other hand the code in Java is a doubly nested loop; but the code in Clojure is a single recursive loop with two recursion points. That’s interesting.

I could write the recursive algorithm in Java like this:

private List<Integer> factorsOf(int n) {

return factorsOf(n, 2, new ArrayList<Integer>());

}

private List<Integer> factorsOf(int n, int d, List<Integer> factors) {

if (n>1) {

if (n%d == 0) {

factors.add(d);

return factorsOf(n/d, d, factors);

} else {

return factorsOf(n, d+1, factors);

}

}

return factors;

}

And then, since this is tail recursive, I could rewrite it as a straight loop.

private List<Integer> factorsOf(int n, int d, List<Integer> factors) {

while (true) {

if (n > 1) {

if (n % d == 0) {

factors.add(d);

n /= d;

} else {

d++;

}

} else

return factors;

}

}

For all intents and purposes this code executes the same algorithm as the standard solution; but it does not have a doubly nested loop. We have transformed the code from a doubly nested loop, to a single loop, without affecting the algorithm.

Is this always possible?

In other words: given a program with a nested loop, is there a way to write the same program with a single loop?

The answer to that is: Yes.

The fact that a bit of code executes within an inner loop could be encoded into a state variable. The outer loop could then dispatch to that bit of code depending upon how that state variable is set.

We see that in the code above. The state condition for the inner loop is n%d==0. Indeed, I can extract that out as a explanatory variable to make my point clearer. I can also extract n>1.

private List<Integer> factorsOf(int n, int d, List<Integer> factors) {

while (true) {

boolean factorsRemain = n > 1;

boolean currentDivisorIsFactor = n % d == 0;

if (factorsRemain) {

if (currentDivisorIsFactor) {

factors.add(d);

n /= d;

} else {

d++;

}

} else

return factors;

}

}

Now all the looping decisions are made at the very top; and the if statements simply dispatch the flow of control to the right bits of code.

That nested if is a bit annoying. Let’s replace all that nesting with appropriate logic.

private List<Integer> factorsOf(int n, int d, List<Integer> factors) {

while (true) {

boolean factorsRemain = n > 1;

boolean currentDivisorIsFactor = n % d == 0;

if (factorsRemain && currentDivisorIsFactor) {

factors.add(d);

n /= d;

}

if (factorsRemain && !currentDivisorIsFactor)

d++;

if (!factorsRemain)

return factors;

}

}

Now we have a nice outer loop that fully determines the execution path up front, and then selects the appropriate paths with a sequence of if statements with no else clauses.

Indeed, we can improve upon this just a little bit more by using more explanatory variables to explicitly name those paths.

private List<Integer> factorsOf(int n, int d, List<Integer> factors) {

while (true) {

boolean factorsRemain = n > 1;

boolean currentDivisorIsFactor = n % d == 0;

boolean factorOutCurrentDivisor = factorsRemain &&

currentDivisorIsFactor;

boolean tryNextDivisor = factorsRemain && !currentDivisorIsFactor;

boolean allDone = !factorsRemain;

if (factorOutCurrentDivisor) {

factors.add(d);

n /= d;

}

if (tryNextDivisor) {

d++;

}

if (allDone)

return factors;

}

}

I think I can make this more interesting by using an enum and a switch.

private enum State {Starting, Factoring, Searching, Done}

private List<Integer> factorsOf(int n, int d, List<Integer> factors) {

State state = State.Starting;

while (true) {

boolean factorsRemain = n > 1;

boolean currentDivisorIsFactor = n % d == 0;

if (factorsRemain && currentDivisorIsFactor)

state = State.Factoring;

if (factorsRemain && !currentDivisorIsFactor)

state = State.Searching;

if (!factorsRemain)

state = State.Done;

switch (state) {

case Factoring:

factors.add(d);

n /= d;

break;

case Searching:

d++;

break;

case Done:

return factors;

}

}

}

Now let’s move the determination of the next state into each case.

private List<Integer> factorsOf(int n, int d, List<Integer> factors) {

State state = State.Starting;

while (true) {

switch (state) {

case Starting:

if (n == 1)

state = State.Done;

else if (n % d == 0)

state = State.Factoring;

else

state = State.Searching;

break;

case Factoring:

factors.add(d);

n /= d;

if (n == 1)

state = State.Done;

else if (n % d != 0)

state = State.Searching;

break;

case Searching:

d++;

if (n == 1)

state = State.Done;

else if (n % d == 0)

state = State.Factoring;

break;

case Done:

return factors;

}

}

}

Ugh. I think we can improve upon this by moving a few things around and gettting rid of those explanatory variables.

private List<Integer> factorsOf(int n, int d, List<Integer> factors) {

State state = State.Starting;

while (true) {

switch (state) {

case Starting:

break;

case Factoring:

factors.add(d);

n /= d;

break;

case Searching:

d++;

break;

case Done:

return factors;

}

if (n == 1)

state = State.Done;

else if (n % d == 0)

state = State.Factoring;

else

state = State.Searching;

}

}

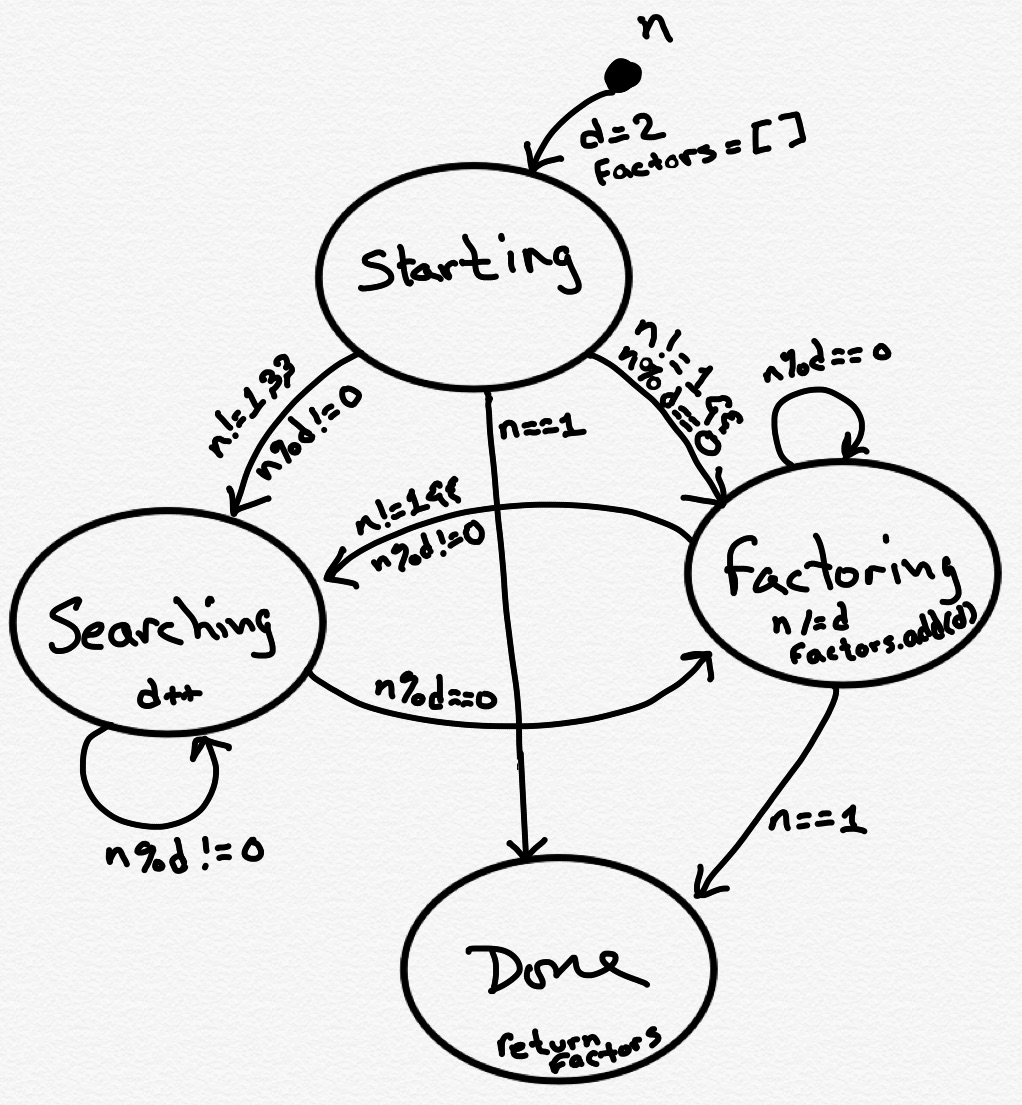

OK, So now the whole thing has been changed into a Moore model finite state machine. The state transition diagram looks like this.

If you look closely you can see the nested loops in that diagram. They are the two transitions on the Searching and Factoring states that stay in the same state. You can also see the how the two loops interconnect through the transitions between the Searching and Factoring states. The Starting state simply accepts n from the outside world and initializes d and factors, and then dispatches to one of the other three states as appropriate. The Done state simply returns the factors list.

This is how Alan Turing envisioned computation in his 1936 paper, which you can read about in Charles Petzold’s wonderful book: The Annotated Turing.

So, we’ve gone from a nice doubly nested loop in Java to a Turing style finite state machine simply through a sequence of refactorings, each of which kept all the tests passing. This transformation from a standard procedure to a Turing style finite state machine could be done on any program at all.

Now let’s go back to the two bits of code that started all this. The Java version:

public List<Integer> factorsOf(int n) {

ArrayList<Integer> factors = new ArrayList<>();

for (int d = 2; n > 1; d++)

for (; n % d == 0; n /= d)

factors.add(d);

return factors;

}

And the Clojure version:

(defn prime-factors [n]

(loop [n n d 2 factors []]

(if (> n 1)

(if (zero? (mod n d))

(recur (/ n d) d (conj factors d))

(recur n (inc d) factors))

factors)))

The finite state machine is entirely hidden in the Java version isn’t it. It’s very difficult to see it peaking out from those nested for loops. But that state machine is much more obvious in the Clojure program. The state is determined by the two if forms, and the appropriate code is executed for each state.

If you can’t see that FSM in the Clojure code, then consider this simple refactoring which makes it even more evident:

(defn factors [n]

(loop [n n d 2 fs []]

(cond

(and (not= n 1) (zero? (mod n d))) (recur (/ n d) d (conj fs d))

(and (not= n 1) (not (zero? (mod n d)))) (recur n (inc d) fs)

(= n 1) fs)))

Why should this be? Why should the Clojure program look more like the FSM than the Java program? The answer is simple. The Java program can save some state information within the flow of control, because it can mutate variables while the loops are in progress. The Clojure program cannot save any state within the flow of control because no variables can be mutated at all. Those state changes are only noticed when the recursive loop is re-entered.

Thus, functional programs tend to look much more like Finite State Machines than programs that are free to manipulate variables.

One last thought. The Java program that implemented the Finite State Machine had only one loop; and that loop was: while (true). That means the loop knew nothing at all about the algorithm it was looping. Thus we can abstract it away from the program itself and envision a language that has no loops at all. No while statements, no for loops, no if statements, and (of course) no gotos. Programs in this language would be written in the FSM style. They would be composed of switch statements that switched on boolean expressions that identified each state. The language system would then simply execute that program, over and over, until told to stop.

Such programs would be naturally functional. For although they could mutate the state of variables, the mutated state would be irrelevant to the flow of control within the program, and could only affect the next iteration of the program. In effect the program would look like a tail-call-optimized recursive function.

Wait… Did I miss the exit?