A few days ago someone tweeted a question asking which of the following PHP snippets was better than the others, or whether there might be an even better approach.

I tweeted my answer in the following cryptic paragraph.

Place the if/else cases in a factory object that creates a polymorphic object for each variant. Create the factory in ‘main’ and pass it into your app. That will ensure that the if/else chain occurs only once.

Others have since asked me for an example. Twitter is not the best medium for that so…

Firstly, if the sole intent of the programmer is to translate:

0->'male',

1->'female'

otherwise -> 'unknown'

…then his refactoring #2 would be my preference.

However, I have a hard time believing that the business rules of the system are not using that gender code for making policy decisions. My fear is that the if/else/switch chain that the author was asking about is replicated in many more places within the code. Some of those if/else/switch statements might switch on the integer, and others might switch on the string. It’s not inconceivable that you’d find a if/else/switch that used an integer in one case and a string in the next!

The proliferation of if/else/switch statements is a common problem in software systems. The fact that they are replicated in many places is problematic because when such statements are inevitably changed, it is easy to miss some. This leads to fragile systems.

But there is a worse problem with if/else/switch statements. It’s the dependency structure.

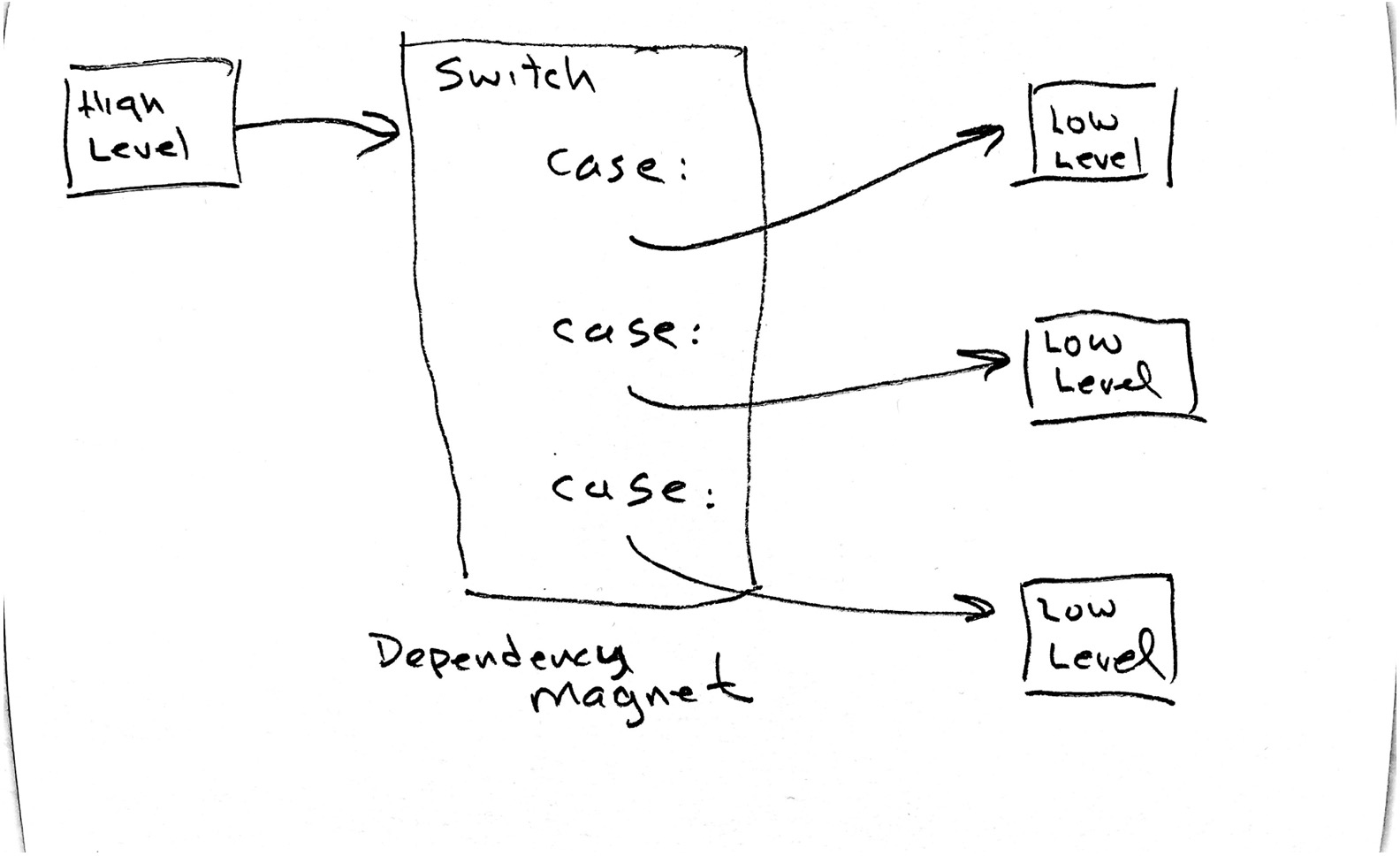

Such statements tend to have cases that point outwards towards lower level modules. This often means that the module containing the if/else/switch will have source code dependencies upon those lower level modules.

That’s bad enough. We don’t like dependencies that run from high level modules to low level modules. They thwart our desire to create architectures that are made up of independently deployable components.

However, the above diagram shows that it’s worse than that. Other higher level modules tend to depend on the modules that contains those if/else/switch statements. Those higher level modules, therefore, have transitive dependencies upon the lower level modules. This turns the if/else/switch statements into dependency magnets that reach across large swathes of the system source code, binding the system into a tight monolithic architecture without a flexible component structure.

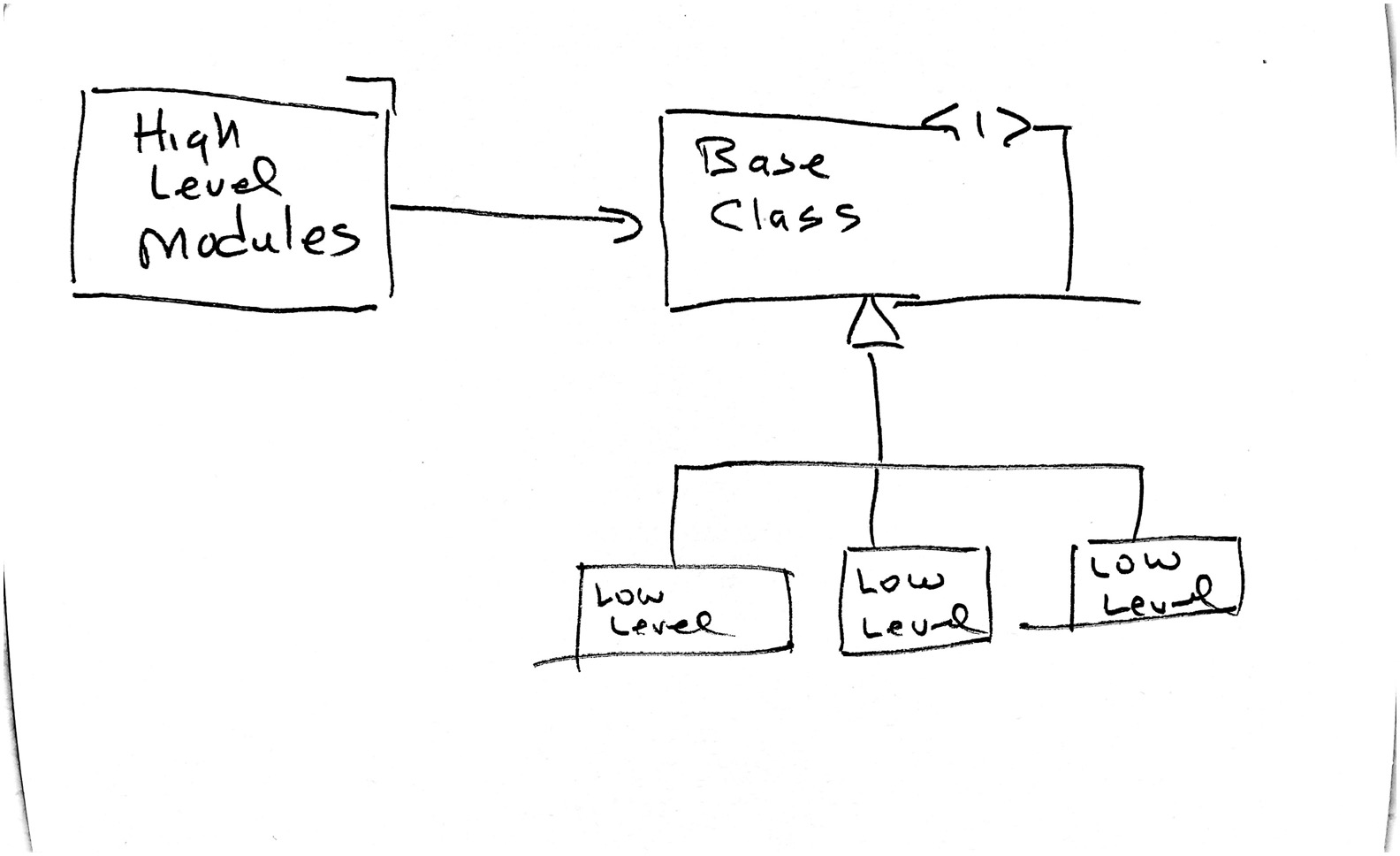

The solution to this problem is to break those outwards dependencies on the lower level modules. This can be done with simple polymorphism.

In the diagram above you can see the high level modules using a base class interface that polymorphically deploys to the low level details. With a little thought you should be able to see that this is behaviorally identical to the if/else/switch but with a twist. The decision about which case to follow must have been made before those high level policy modules invoked the base class interface.

We’ll come back to when that decision is made in a moment. For now, just look at the direction of the dependencies. There is no longer any transitive source code dependency from the high level modules to the low level modules. We could easily create a component boundary that separates them. We could even deploy the high level modules independently from the low level modules. This makes for a pleasantly flexible architecture.

Another point to consider is that the if/else/switch and the polymorphic implementations both use table lookups to do their work. In the case of an if/else the table lookup is procedural. In the case of a switch most compilers build a little lookup table. In the case of the polymorphic dispatch the vector table is built into the base class interface. So all three have very similar runtime and memory characteristics. One is not much faster than another.

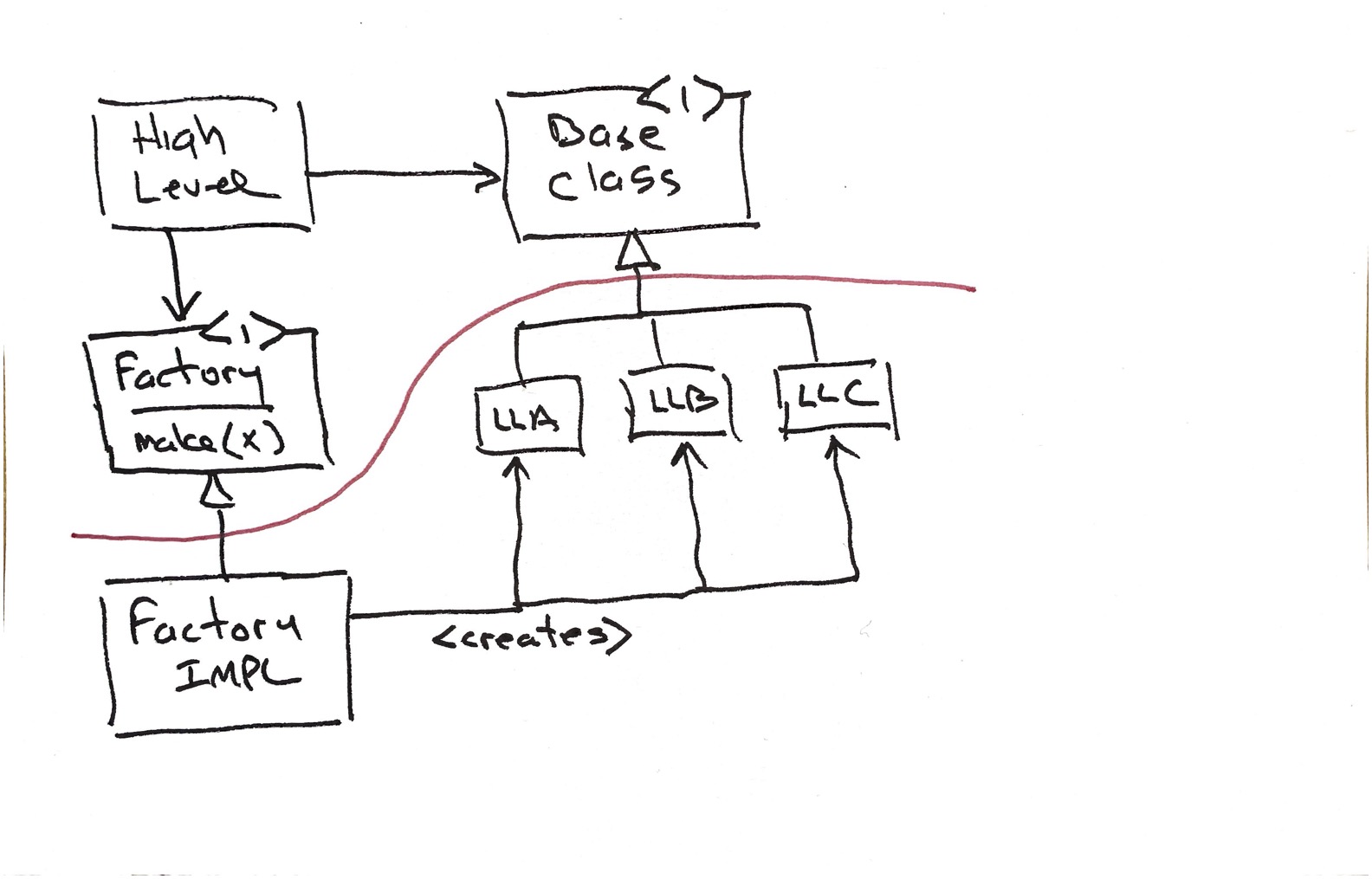

So where does the decision get made? The decision is made when the instance of the base class is created. Hopefully that creation happens in a nice safe place like main. Usually we manage that with a simple factory class.

In the diagram above you can see the high level module uses the base class to do its work. Every business rule that would once have depended on an if/else/switch statement now has its own particular method to call in the base class. When a business rule calls that method, it will deploy down to the proper low level module. The low level module is created by the Factory. The high level module invokes the make(x) method of the Factory passing some kind of token x that represents the decision. The FactoryImpl contains the sole if/else/switch statement, which creates the appropriate instance and passes it back to the high level module which then invokes it.

Note, again, the direction of the dependencies. See that red line? That’s a nice convenient component boundary. All dependencies cross it pointing towards the higher level modules.

Be careful with that token x. Don’t try to make it an enum or anything that requires a declaration above the red line. An integer, or a string is a better choice. It may not be type safe. Indeed, it cannot be type safe. But it will allow you to preserve the component structure of your architecture.

You may well be concerned about a different matter. That base class needs a method for every business rule that once depended upon the if/else/switch decision. As more of those business rules appear, you’ll have to add more methods to the base class. And since many business rules already depend upon the base class they’ll have to be recompiled/redeployed even though nothing they care about changed.

There are many ways to resolve that problem. I could keep this blog going for another 2,000 words or so describing them. To avoid that I suggest you look up The Interface Segregation Principle and the Acyclic Visitor pattern.

Anyway, isn’t it fascinating how interesting a discussion of a simple if/else/switch can be?